There is an increasing sense of urgency about how Australia’s energy system will transition to one that can operate with periods of 100% instantaneous renewable energy.

Newly appointed AEMO Chief Executive Daniel Westerman, has set AEMO the goal of a grid ready for this task by 2025.

Ambitious goals are necessary to spur action but they only cover part of the story. For tens of millions of consumers, how we get there will be just as important as when.

The fast pace of change has exposed the challenge of coordinating a transforming national energy system across many stakeholders: industry bodies, state and federal governments, and private investors. As different jurisdictions pursue their own energy policies and investments, the totality of all this change becomes harder to keep track of. It is now difficult for even experts within the system to keep in mind how these interventions, policies, and investments interact and whether there is duplication.

Why is that a problem? If the policy landscape seems unclear it may be tempting to keep investing in more infrastructure to ensure reliability and stability. And excess infrastructure will result in an unnecessary financial burden on future generations of consumers.

Some investment will be needed. But how much? And at what cost for who? To what extent should we focus on demand flexibility as a low-cost, just-as-reliable alternative to expensive new infrastructure? Answering these questions requires a cohesive and coordinated national strategy; one that starts with consumer needs and expectations, including just how much consumers are willing to pay for reliability.

An increasingly complex and diverse landscape

Energy Consumers Australia and KPMG recently released Australia’s Energy Transition (AET): a Snapshot of the Changing Policy Landscape, a report that summarises the suite of policies being implemented by individual governments across Australia. Each state government is facing different pressures and challenges in relation to its electricity supply, whether it be the pending retirement of significant generation or addressing system strength issues when there is more solar power being generated than consumer demand for energy. This has prompted a greater level of individual jurisdictional involvement in electricity markets, and an apparent move away from the Australian Energy Market Agreement that outlined a cooperative, coordinated approach to energy policy.

At the same time, AEMO’s Integrated System Plan is proposing significant investment in transmission across the NEM. A more integrated and connected system helps improve system resilience as well as allowing low-cost generation to flow between connected states.

Coordinating multiple stakeholders in the national energy system to ensure fit-for-purpose investment in the energy system reflects a significant challenge. A careful balance is required to “keep the lights” on while making sure that unnecessary or duplicative investment does not result in financial burden on future generations of consumers.

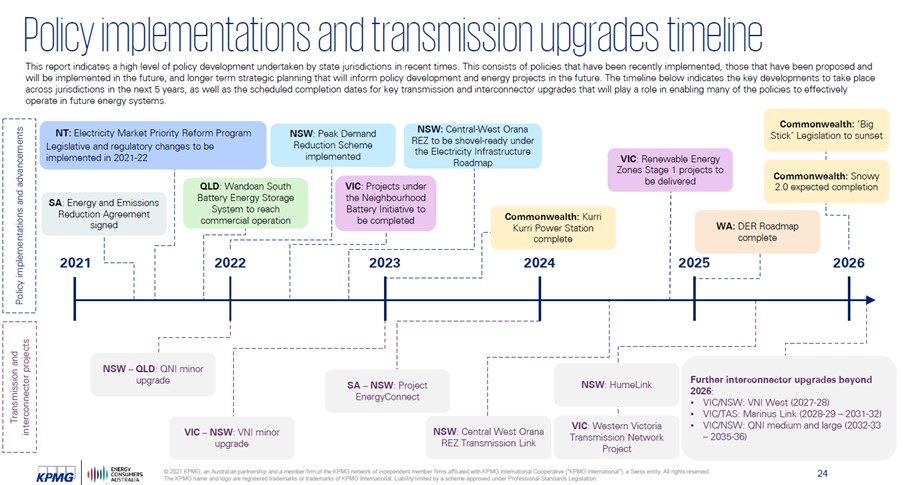

Figure 1, below, plots some of the key investments and policies expected over the next five years. By gathering all the current and future changes to the energy system at a national level we begin to start to assemble a picture of the investment landscape.

Figure 1. Policy and investment timeline found on page 24 of Australia’s Energy Transition: A Snapshot of the Changing Policy Landscape

Figure 1. Policy and investment timeline found on page 24 of Australia’s Energy Transition: A Snapshot of the Changing Policy Landscape

Will customers end up paying for unnecessary investment?

Each policy and investment decision, considered in isolation, may seem the right thing to do. But we operate in an interconnected system, designed to allow the cheapest electricity to flow to all customers in the national electricity market. What happens in one jurisdiction will therefore impact outcomes in other jurisdictions.

For this reason, we need to consider all these individual policies not in isolation, but as part of a broader system. We must do so knowing that any overlap or duplications might result in additional costs for consumers.

The Australia’s Energy Transition report provides the current state of play of each jurisdiction’s energy landscape. Queensland and Victoria are currently net exporters of energy, and both have large Renewable Energy Zone developments planned to maintain or increase generation capacity despite retirement of coal-fired generation. In Tasmania, there is a focus on building the “battery of the nation”, as the state has an advantage in hydro and water resources. By building up renewable energy generation, Tasmania can expect to supply mainland jurisdictions with clean energy.

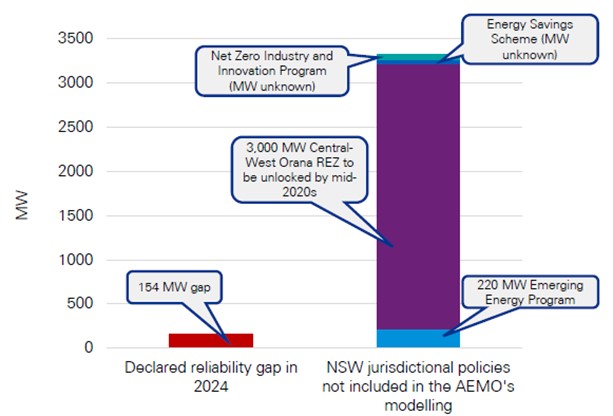

NSW has traditionally been a net importer of energy, but a snapshot of the current jurisdictional energy landscape suggests planned generation is more than enough to meet its own expected peak demand, even when AEMO had declared a reliability gap for NSW in 2024. This means that NSW will potentially be producing generation beyond forecasted supply requirements for customers.

So, if states are all planning to meet their own reliability requirements and more, are we missing key opportunities to coordinate and reduce additional costs to consumers?

Figure 2. NSW- declared reliability gap vs. capacity to be unlocked by projects not included in AEMO’s modelling in 2020. (p.10 Australia’s Energy Transition: A snapshot of the Changing Policy Landscape)

Figure 2. NSW- declared reliability gap vs. capacity to be unlocked by projects not included in AEMO’s modelling in 2020. (p.10 Australia’s Energy Transition: A snapshot of the Changing Policy Landscape)

In 2020, AEMO declared a reliability gap in NSW for 2024 due to the retirement of Liddell Power Station. At the time this gap was declared, AEMO’s modelling to forecast this gap did not take into account the large number of jurisdictional policies which had been announced as seen in Figure 1. In the 2021 ESOO AEMO has changed its assessment, incorporating new generation, storage, and transmission development commitments, no longer forecasting a reliability gap for NSW. This emphasises how critical it is to account for the wide range and breadth of current energy policy in overall system planning.

A future energy system that consumers can believe in

The Australian energy system is currently undergoing the most rapid change in its history. Governments, industry, and consumers are all contributing in their own way to movement towards meeting carbon emission targets while system actors attempt to mitigate any risks to energy supply due to the economic shutdown of traditional coal and gas power plants.

Policy decisions regarding new power generation, phasing out of fossil fuels, upgrading outdated networks, and options for energy storage are being made across different jurisdictions and by government and private institutions, resulting in a complex and sometimes disjointed landscape. Each jurisdiction faces specific challenges, environments, and pressures, and identifies opportunities (and has responded as they see necessary). But to achieve the best outcomes for all Australian consumers we need a whole-of-system approach.

Imagine trying to raise a big top tent with a hundred hands, where each new tentpole inserted or rope pulled tight can unbalance what has already been done, collapsing parts of the structure, leaving a wobbling forest of canvas and poles. Like the tent, the national energy network is highly interconnected so that each local decision can have a national impact. We need a whole-of-system approach to coordinate the rapid changes necessary to meet the urgent demands of carbon neutrality and network stability over the next two decades at the lowest possible cost to consumers.

A clear and coordinated approach will be crucial in maintaining consumer confidence and support in energy markets. After all, getting the big top up is of little use if the entrance fee is too high.