The #energycrisis has been doing the Energy Market no favours in reassuring Australians that their energy needs are in safe hands. The suspension of the market in June and increasing prices have had an obvious impact, sapping consumer confidence and increasing concern about affordability.

But have these events brought about the changes in consumer behaviour that some have predicted?

Following the ‘crisis’ we heard predictions that interest in technology relating to energy independence would skyrocket – with talk in June of companies who sell solar panels and batteries having to employ more staff to keep up with the calls coming through. Logically this made some sense: If consumers don’t feel the energy market is working in their interest, have seen rising prices and reliability issues, why would they stick around? Wouldn’t they be keen to take charge of generating and storing their own electricity?

The truth is, it might not be so simple. Our newly released Energy Consumer Behaviour Survey (ECBS), for which fieldwork concluded in mid-August, tells a more complicated story.

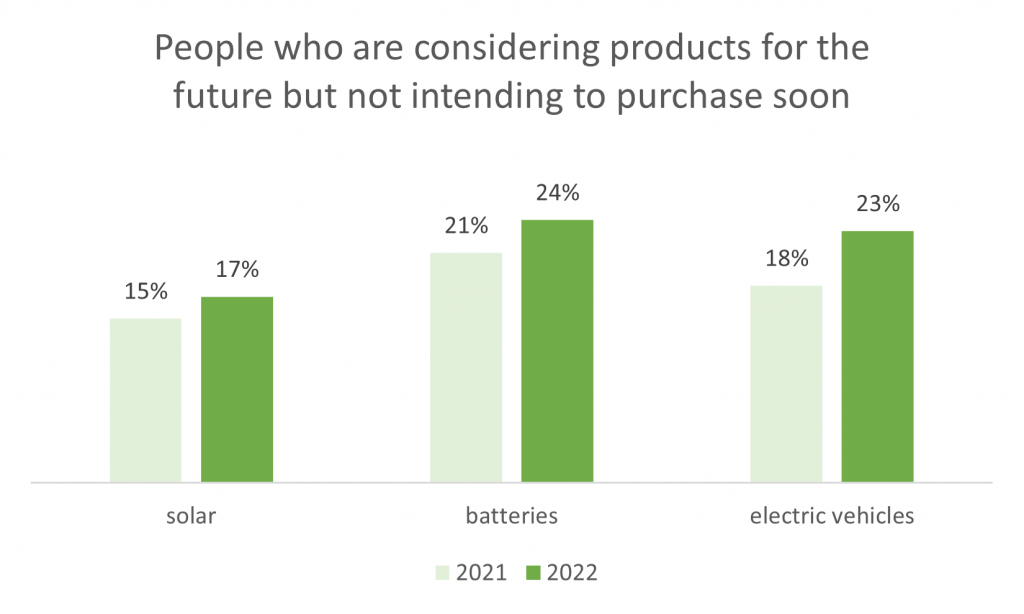

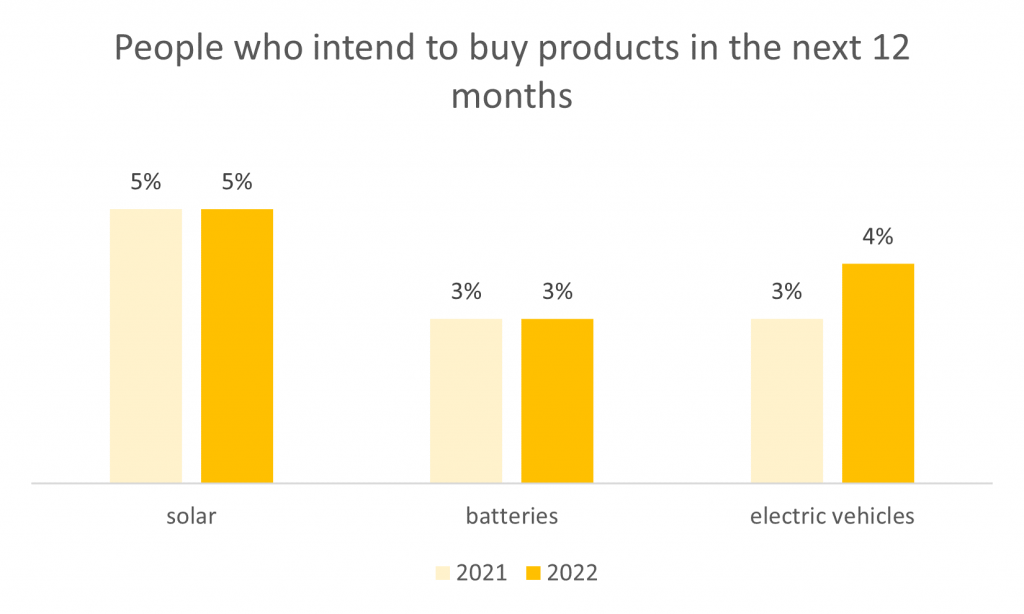

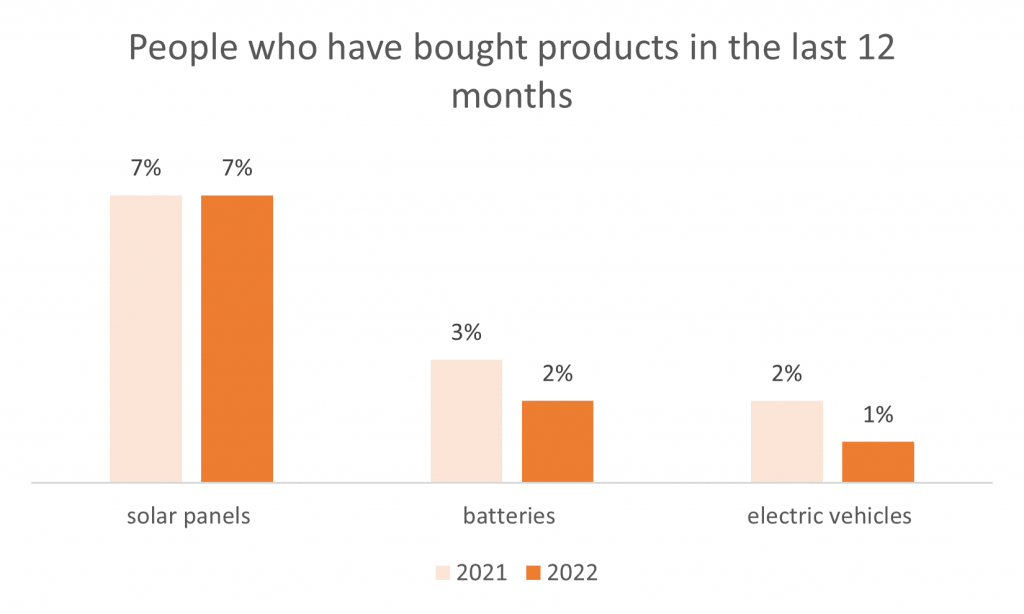

While the ECBS finds the number of people considering solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles has risen, this interest is mostly not translating into action. The number of people intending to buy these technologies in the next 12 months remains about the same as the year before, while the number who have bought them in the last year is static or even decreasing.

More recently, claims of a 'solar boom' have surfaced again, after power company leaders, including Alinta's Jeff Dimmery, predicted tariffs could jump by as much as 35 per cent in 2023. In this case there is some evidence of at least a short term boost, with total installed capacity in Australia in September about 17% higher than the year-to-date average. Analysts have observed, though that a contributor to this is people opting for larger capacity systems and that supply chain, labour issues and installation costs could mean that any demand spike quickly cools.

If nothing else we have a confusing picture here. So what is going on? Are consumer energy resources poised to boom or have we reached a point of gridlock -- where those who can, mostly have and those who remain are caught in a disconnect between intent and action?

The solar story

We hear it all the time – Australia is leading the world with rooftop solar adoption. The success story of Australian rooftop solar is that 33% of us have it. Of course, that also means that 67% of us don’t. The story our data tells is that those early adopters, who have the means, motive and opportunity to take up this technology, to a certain extent already have.

If they are the 33%, the remaining 67% can be separated into two broad groups: those who are interested but gridlocked through financial difficulties, information deficit or living circumstances, and those who aren’t in the market and aren’t even thinking about it.

Most people without, aren't thinking about it

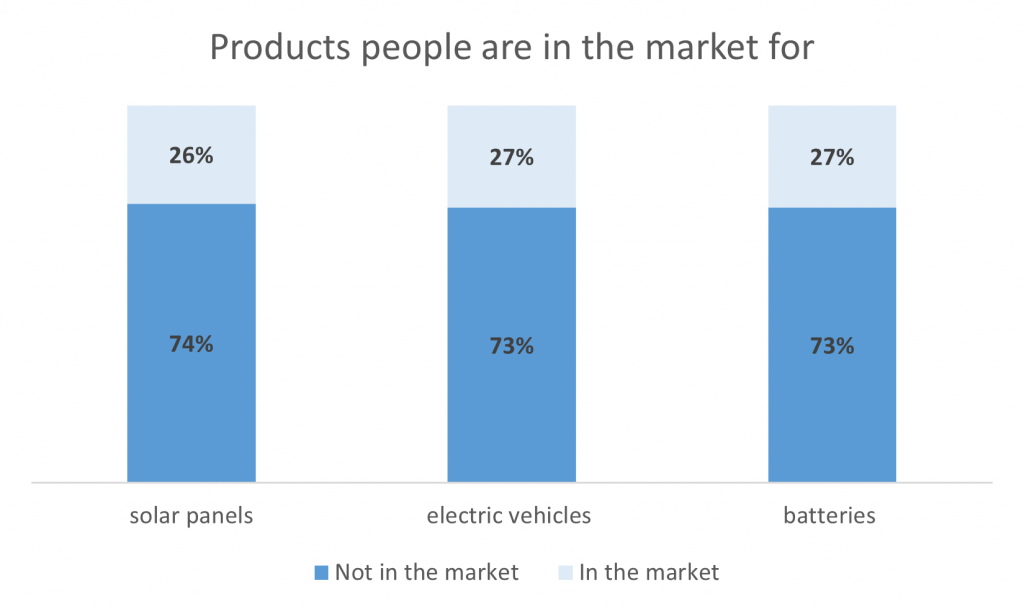

According to the ECBS, of the households who don’t have solar only 26% are intending to purchase or considering. That means 74% are not ‘in the market’. We also see this reticence play out similarly across other technologies such as home batteries and electric vehicles.

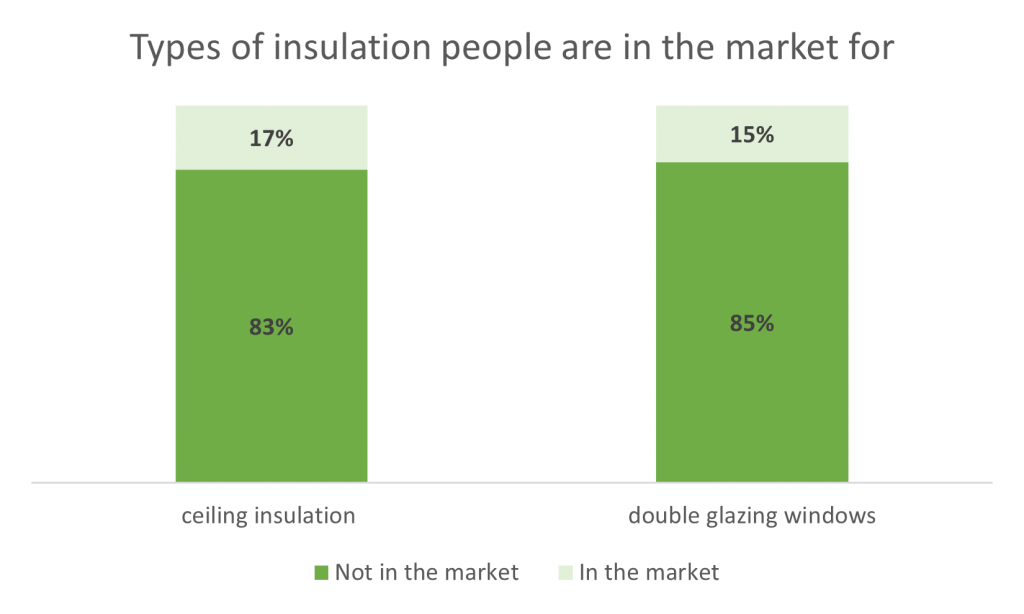

This phenomenon doesn’t just apply to new technology – energy efficiency mechanisms such as insulation can dramatically improve the thermal comfort of a home, meaning it requires less heating and cooling. But only 17% of those who lack ceiling insulation are considering installing it, while for double glazed windows the figure is 15%.

If we are expecting consumers to continue investing in technology such as solar, batteries and EVs or even retrofit their homes to save on long-term energy costs, these numbers do not look promising.

So why are so many people not in the market?

Because they face barriers

These barriers are sometimes as simple as the upfront costs of appliances, tech and insulation. But they can be other things too. Renters or people living in apartment buildings may not own or have access to a driveway or roof. For these people it can be a case of ‘I want to but I am not able’.

We can also see a cohort of people who are able but not ready. Barriers for these people might include current information gaps or lack of trust. Both tend to amplify doubt and uncertainty and frustrate action. Our ‘Pulse Survey’ in August revealed half of Australians (49%) believe they don’t have access to the information they need to make decisions around energy.

More help is needed, and it should be led by governments and coordinated and funded to work on a national scale. That is a big part of the future agenda Energy Consumers Australia is advocating for right now.

Who are the people facing most barriers?

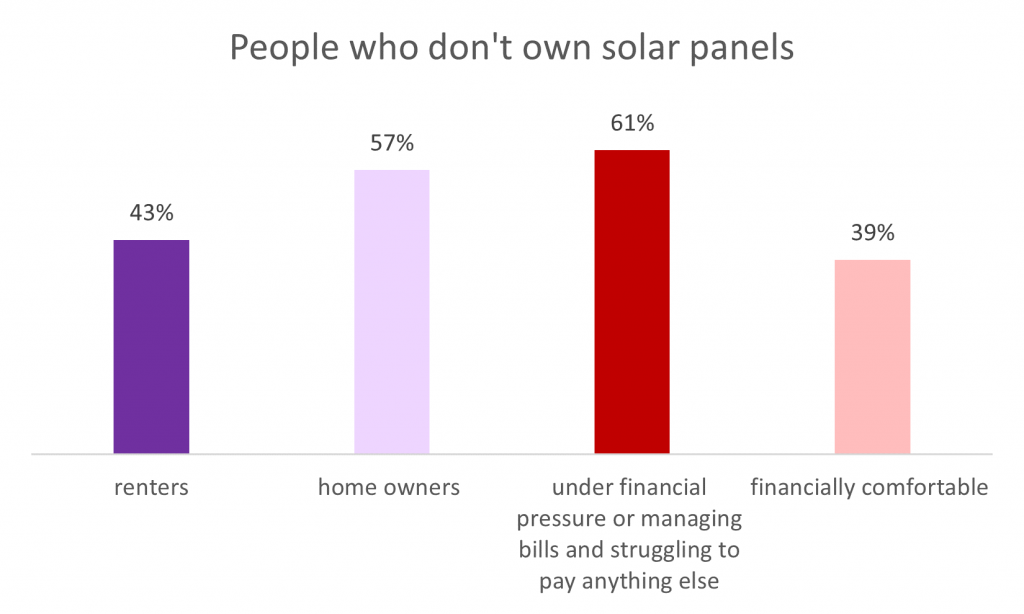

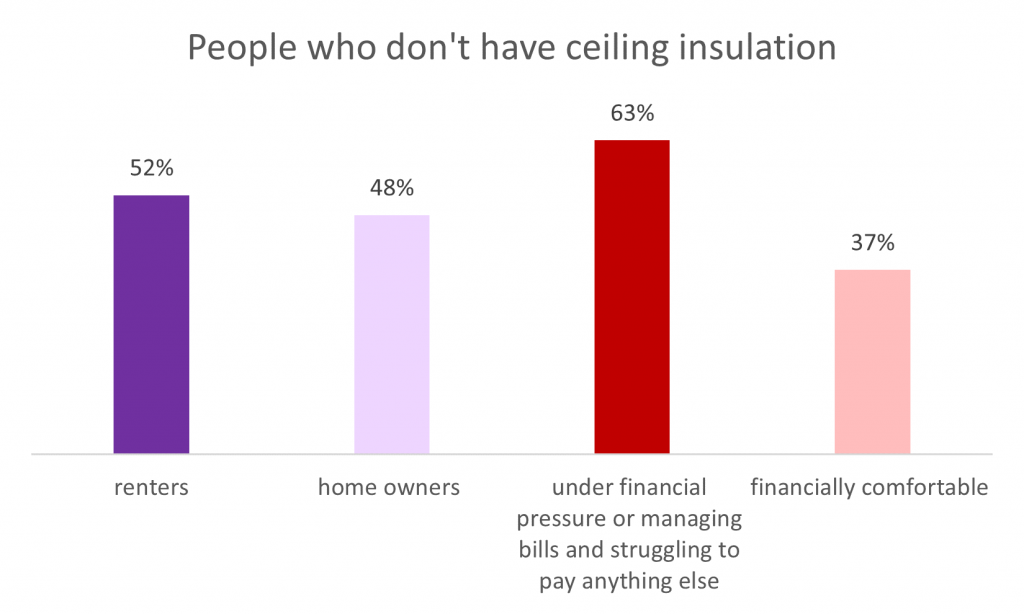

The ECBS data makes clear that those who are renting (30% of the population according to latest census data) are less interested in adding new energy technologies. Those who are under financial pressure are also disproportionally affected.

Of the people who don’t have solar panels, 43% are renters and 61% are under financial pressure. Of those who don’t have ceiling insulation, 52% are renting and 63% are under financial pressure.

Some of these barriers may be insurmountable. Those who are renting might not be able to simply buy their own home to have more confidence in installing solar. And no matter how much new tech comes down in price – it might always be out of reach for some people and never be seen as a priority.

But there are things that can and should be done. And we will need to start doing them if we are to secure an energy transition that is fair and inclusive for all Australians.

Breaking the gridlock

Despite the motivating forces brought by the energy crisis we can see an element of gridlock when it comes to adoption of these new technologies and measures. Consumers, through their lack of action, are telling us that they need more support in moving from interest to action. They need concrete assistance and trusted advice to give them the confidence to proceed.

That’s why it’s critical that we focus our efforts twofold: First, on making sure we are removing the barriers that can be removed – with supports and incentives and access to trusted information for people who are in a position to adopt these technologies. Second, on making sure we have an inclusive energy transition where other benefits are available to those for whom the barriers to participation are higher.

That should include subsidising housing insulation to reduce heating bills, it should include direct assistance with getting off gas and electrifying appliances – making sure consumers under financial pressure are not left stranded on a gas network that becomes increasingly expensive as those who can afford to electrify do. It should include new standards and mechanisms that encourage, incentivise and even require landlords to introduce energy efficiency measures that can deliver bill savings (as well as health and comfort benefits) for tenants.

Getting to a point where 50% of the population has access to rooftop solar would be a huge jump from where we are now and will require many of the measures detailed above. But even if we do it, half of all Australians will still not have this access (and the benefits that come with it). We can’t afford to have a system of haves and have nots, where the have nots are represented by half the population paying more for energy and unable to do anything to change their circumstances.

That outcome wouldn’t represent gridlock so much as a car crash of unintended consequences and harms. The time to act to prevent that happening is now.