There is a tendency to think of the energy divide—the difference between those who can easily access clean, reliable and affordable energy—as something experienced only by those on low income, or who are experiencing financial stress. Indeed, these consumers are the most likely to experience the divide, and feel its impacts most keenly. But on closer inspection, the risk of the divide growing, and more consumers falling into it, is growing day by day.

As we face the energy transition head on, we have a real opportunity to close the energy divide for good. Realising the benefits of low-cost, renewable electricity for all consumers is well within our reach. However, existing and emerging barriers to participation in the transition mean that we risk not only leaving those already in the energy divide behind, but widening the divide even further.

Read the full report (PDF, 768.68KB)

The energy divide is already hurting consumers, and disproportionately affects those who face the highest barriers to inclusion

It’s a distressing truth that for low-income consumers and/or those experiencing vulnerability the energy divide is more of a gulf. Accessing clean, reliable and affordable energy is harder for these consumers than for those with the means, capacity and agency to do so. It’s also clear that the impacts of the energy divide on these consumers is catastrophic—for many, it can include complete disconnection from energy, the forfeiting of other essentials like groceries to afford bills, compounding debt and the mental health impacts that come with it, and serious health impacts for those who can’t heat and cool their homes appropriately.

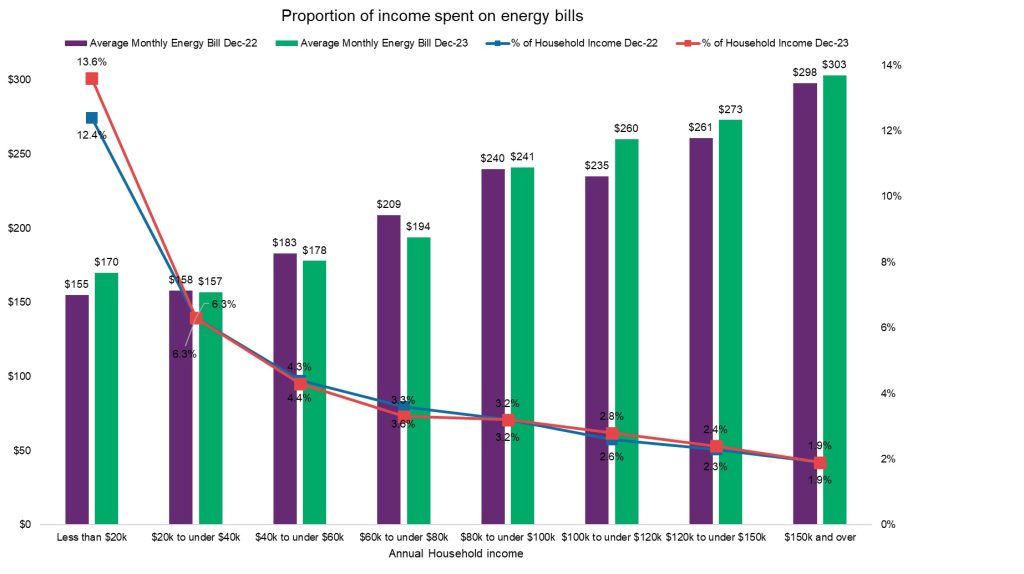

Our Energy Consumer Sentiment Survey (ECSS) shows that low-income households are consistently paying a greater portion of their income on energy than their higher earning counterparts. Results from December 2023 indicate that for the lowest income households (below $20,000/year), energy costs represent 13.6% of their total income, an increase of 1.2% compared to December 2022. This is over five times more than the proportion of income spent on energy by the highest earning group.

This graph paints a stark picture—for those paying the highest proportion of their income on energy, it’s likely that once other essentials are paid for, there is little, if anything left for discretionary spending, including the high upfront costs of investing in energy efficient upgrades for their homes.

Moreover, as our Stepping Up report found, it’s likely that the proportion of income spent on energy by the lowest income earners will continue to grow in the transition, as they wear the costs of inefficient homes and the gas network. Meanwhile, the proportion paid by the highest earners will likely continue to fall as more wealthy consumers exit the gas network and are able to install energy efficient appliances and even generate and store electricity in their own homes.

This is due to the huge savings that can be made through the transition with more energy efficient homes. ClimateWorks research has found that Australian households could save up to $2,200 a year on energy bills by upgrading homes built before 2003 with better insulation and electrifying appliances and heating. Meanwhile, Solar Victoria estimates that installing solar panels can save the average Victorian household $1,073 on their annual energy bills, while in NSW, households can save up to $600 a year on household electricity bills, or up to twice as much as the Low Income Household Rebate ($285/year) by installing solar.

Emerging drivers of the energy divide risk exacerbating its impact on those already in it, threatening to leave yet more consumers behind

According to ABS data, around 1 in 3 homes in Australia are rentals, and about half of these have a gas connection. This means that 1 in 6 Australian households are reliant on their landlord’s participation in the energy transition—for which there is currently little incentive.

Our ECSS tells us that renters are less likely to live in homes with energy efficient technology, compared to homeowners who are more likely to consider buying an electric vehicle and converting to a fully electric home. As renters are more likely to experience financial stress than homeowners, those already at a disadvantage are the ones with the least capability to absorb rises in energy prices and the health implications of inefficient homes.

For anyone living in a rental property, there is a huge risk of being left behind in the energy transition if policy settings don’t incentivise landlords to make energy efficiency upgrades to their property investments.

Income is only one metric for measuring the energy divide, but we increasingly need to interrogate other barriers to participation in the energy transition if we want to close the divide for good

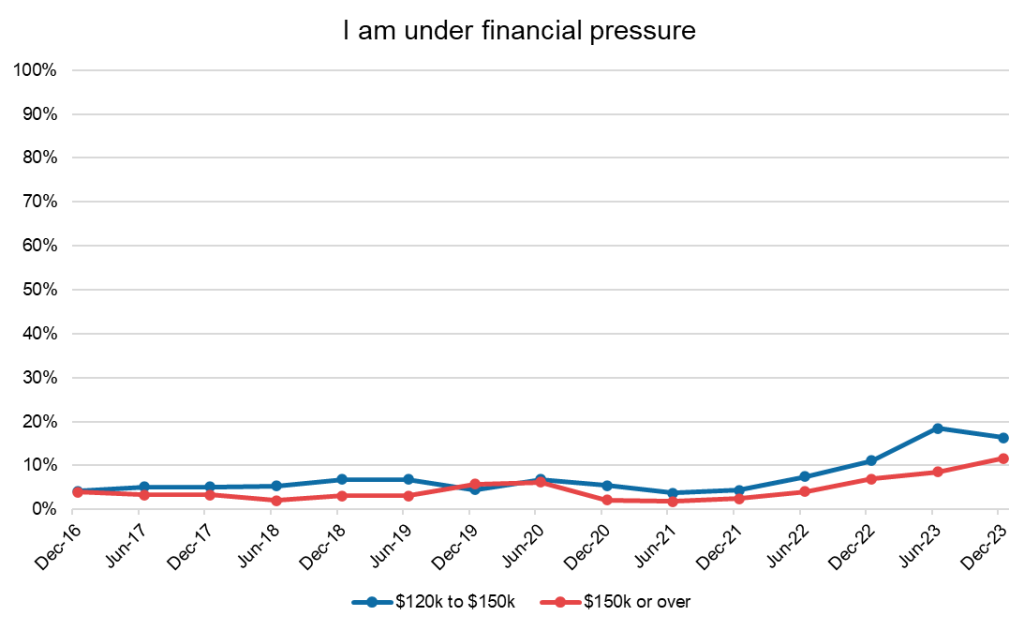

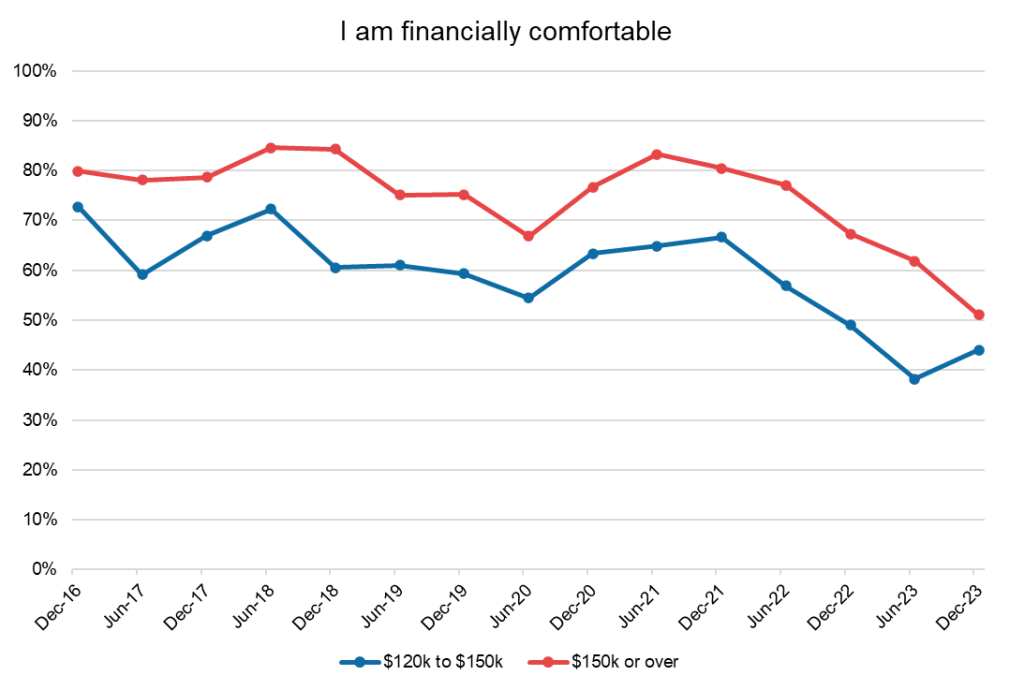

Across all low- and middle-income levels, consumers are increasingly self-identifying as experiencing financial pressure. Our ECSS data shows that around 20% of all consumers are experiencing financial pressure, and that in each income bracket, at least 50% of consumers tell us they are either under financial pressure or managing to pay bills with nothing left over. Interestingly, the perception of being under financial pressure is growing among higher earning consumers.

Correspondingly, our data shows a sharp decline across most income brackets as those who identify as financially comfortable, including those earning higher incomes.

Simultaneously, recent RBA data shows that “on average, households with a mortgage have experienced a significant decline in spare cash flows... For these households, higher interest costs have reduced their cash flow by more than the rise in inflation has.”

Current rebates for energy efficient upgrades may therefore no longer be fit-for-purpose based on arbitrary income thresholds. In Victoria, for instance, the solar rebate is currently available to homeowners and rental households earning under $210k before tax. While on paper, this might seem like a high income, those households might not always have the left-over capital to invest.

For instance, a homeowning household earning under that threshold could now be facing mortgage stress and cost of living pressures including bills, groceries, childcare and schooling costs, compounding student loan debt and low wage growth. They are unlikely to have enough left at the end of the day to invest in major energy efficient upgrades like solar panels and heat pumps. Similarly, a rental property with multiple residents could easily earn above that threshold (even if each resident is individually earning a ‘low’ income)—precluding a landlord from accessing available rebates. Even a landlord who is interested in making their rental property energy efficient could be disincentivized from doing so without access to these rebates.

So even those who appear, based on their income, to have the financial capital to participate in the energy transition, might in reality face significant cost barriers to participation. Cost of living pressures and household debt are therefore likely to be another driver of the energy divide, as a lack of spare cash flow for investment in energy efficiency upgrades means that many mortgage holders that fall into this group are at risk of being left behind in the transition.

So what can we do about all this?

Our research tells us that the number of consumers at risk of being locked out of the energy transition is rapidly increasing. For those already in the divide, and for many of our most vulnerable consumers, its impact will worsen.

It is incumbent on us and policy makers to better understand the drivers of the divide and ensure support to help people participate in the energy transition is fit for purpose. This could include:

- Addressing the divide caused by the proportion of energy spent on income, by preferencing energy efficiency support and upgrades for those consumers and mechanisms to ensure people can afford their energy, such as a social tariff for low-income consumers.

- Implementing meaningful incentives (PDF, 2.23MB) for landlords to ensure rental properties receive the energy efficient upgrades they need.

- Re-assessing income thresholds for energy efficiency rebates and subsidies based on what we know about new and emerging drivers of the energy divide, to ensure they are fit-for-purpose and supporting all consumers who need financial support to transition to do so.

The energy transition promises low-cost, efficient and reliable energy for all—but we need to ensure it is designed and delivered for and with consumers to ensure that no one is left behind.