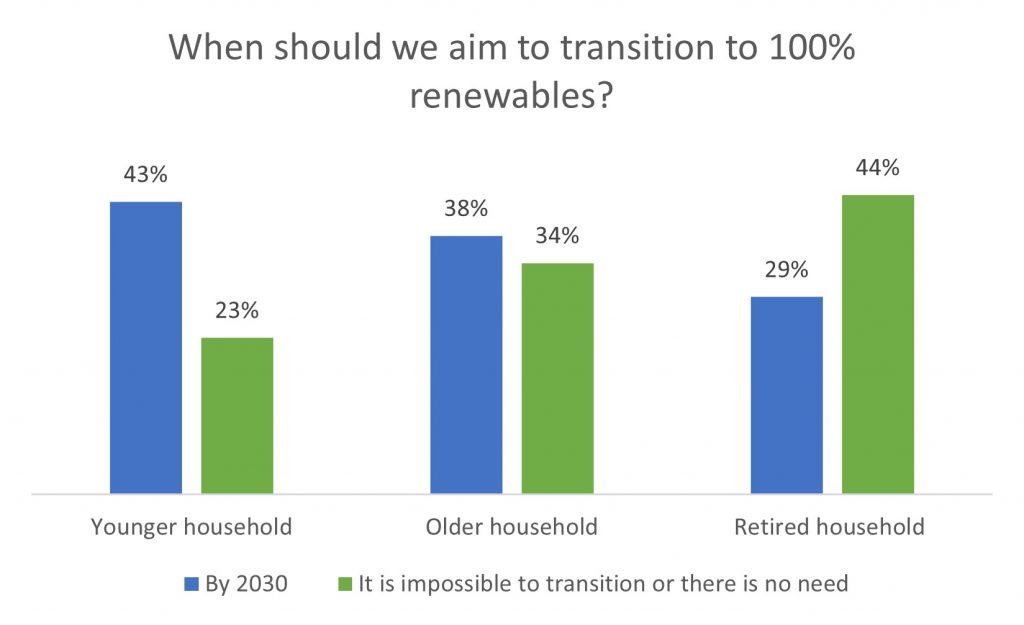

As the saying goes, age is just a number. But could your age influence your view on the energy transition to renewables? Our recent June 2023 Energy Consumer Sentiment Survey (ECSS) data shows statistically significant differences between the youngest and oldest participants in supporting a fast transition to 100% renewables. More younger people, compared to their older counterparts, think we should aim for a faster transition. On the flip side, the percentage of participants surveyed who think it is impossible to transition, or that there is no need to transition to renewables increases with age (see Figure 1 and 2).

These are, of course, only statistical generalisations. It would be bold to assume there aren’t older renewable enthusiasts, and die-hard coal fans in their early twenties. And there are many more nuanced complexities surrounding the debate on renewables. Nevertheless, our data clearly shows generational differences in attitudes towards the energy transition.

Terms such as boomers, millennials and Gen Z are often thrown around when the argument is pitted as young vs old. In this context, the ‘generational gap’ – the difference in attitudes or beliefs between people of different generations – becomes particularly important. Rapid changes over time in terms of popular culture, political movements, the state of the economy, technological advancements, changes in physical environment, societal values and norms can all contribute to the generational gap. This is useful context to keep in mind when we unpack why people of different generations can hold such strong views and how these views may differ.

Due to the methodology for the ECSS, the age brackets displayed don’t fit neatly into the traditional generational breakdowns described above. Instead, our analysis groups respondents as younger households (aged under 44), older households (aged over 44), and retired households (retirees).

Too fast, too slow, or not needed?

In order to meet our net-zero targets, Australia will have to transform our energy system from one that is largely carbon intensive to one that is based on renewable forms of energy production. The key debate has thus shifted from if we need to transition, to how we will transition, and more specifically, how fast we should transition. Those advocating for a fast transition argue that we need to transition immediately to avoid catastrophic consequences of climate change. While those supporting a slower transition argue that it will be too costly to transition at a rapid pace because it will require expensive upgrades to existing infrastructure. These two key arguments were presented to around 2,000 Australian households in our survey to test when they think Australia should aim for a 100% renewable energy system.

As Figure 1 shows, when it comes to supporting a transition by 2030, young households are most in favour.

Figure 1: Perceptions on the speed of the transition. N=2120, young household 10%, older household 26%, retired household 43%

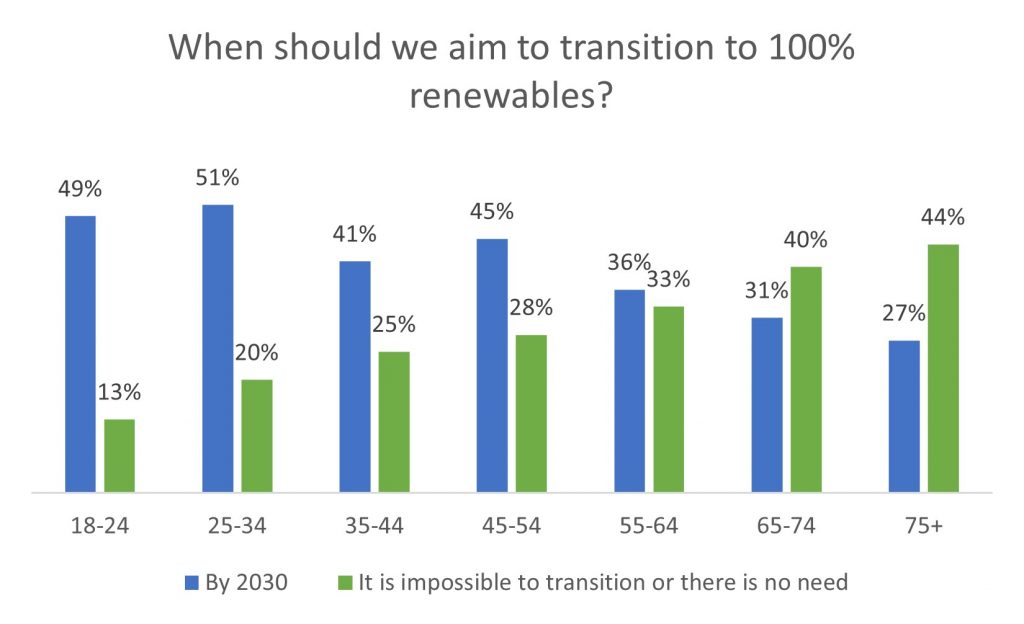

We can break this down further to fully understand how age plays into this. As Figure 2 shows, almost half of 18-24 year olds and just over half of 25-34 year olds surveyed think we should aim to transition to renewables by 2030. In contrast, close to half of 75 and overs surveyed think it is impossible or there is no need to transition to 100% renewables.

Figure 2: Analysis by Age. N=2120, 18-24 (2%) 25-34 (8%) 35-44 (13%) 45-54 (17%) 55-64 (23%) 65-74 (25%) 75+ (12%)

Why young people want a quick transition

When considering why these generational differences may occur, we must recognise that conversations around energy production, climate change, and our net-zero emissions targets are inherently interlinked.

Unlike previous generations who largely viewed and understood climate change as something abstract (if indeed they considered it at all), younger people are more acutely aware of climate change and its day-to-day impacts. Someone who is 18 years old today will be 45 in 2050, so climatic projections to 2050 are not simply ‘potential forecasts’ for them but will be realities they experience. Young people are going to live with the impacts of increasing extreme weather and natural disasters over their lifetime and therefore may view the issue more seriously and see the need to act quickly. Millennials and Gen Z are also more likely to have learnt about climate change at school or university, a relatively new addition to the National Curriculum that older Australians didn’t have access to. These factors may all be driving the positive sentiment towards renewable resources as a key part of the future energy system for younger Australians.

Planning for a certain, not imagined, future

Given the vast generational differences in opinion, what this analysis also brings to light is the need for policy makers to think about young people and their role in the transition. Policy makers need to start asking questions like: What do young people value and want out of a future energy system? What energy attitudes and behaviours will they adapt as they themselves get older? How will they engage or disengage with different energy products and services over time?

For instance, a UK study conducted by the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (OFGEM) focused on the attitudes and behaviours of young energy consumers aged 16-24. They found that this cohort were more likely to own and adopt smart technology, and were also more open to using energy in new and flexible ways. This is an invaluable insight when we consider how the energy system is evolving and what this system will ask of consumers when it comes to energy consumption and production. It would be wise to stop and think, who are we really asking this from? Who are these ‘future’ energy users?

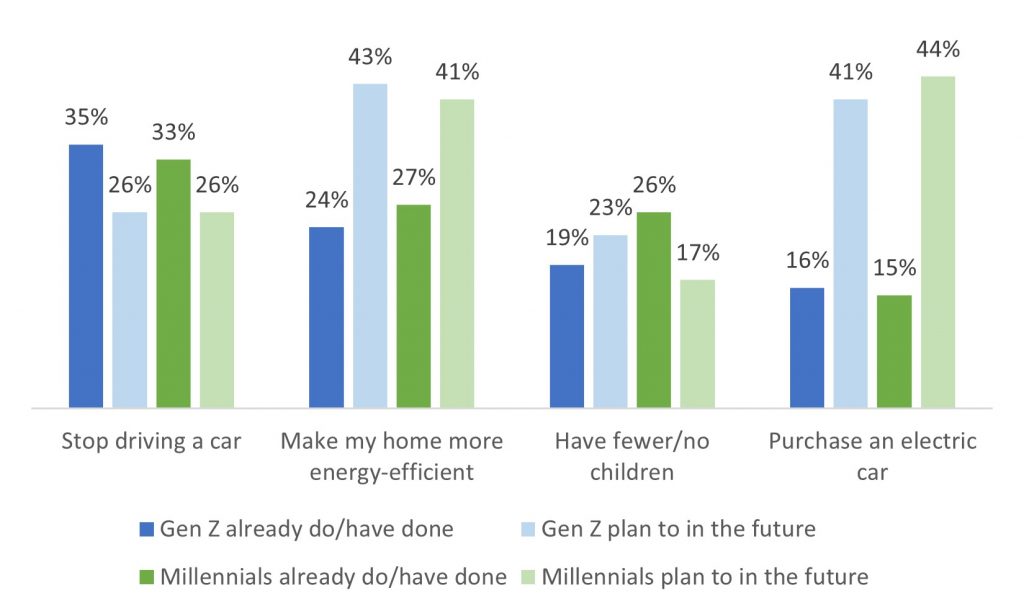

Equally helpful to consider are the broader changes in behaviours and attitudes of young Australians. For instance, young people are less likely to own a car, are more interested in car sharing services, and are even delaying obtaining a driver’s licence. They are more likely to rent, live in share houses, are continuing to live with parents for longer or are boomeranging back to parental homes. We are also seeing women having fewer children, and at an older age. There are also several studies on climate anxiety, also called eco-anxiety, solastalgia, eco-guilt, or ecological grief becoming more prevalent in young people. A recent global study into Gen Z and millennials revealed climate change as a major stressor for these groups, with 60% of Gen Zs and 57% of millennials saying they have felt anxious about the environment in the past month. These concerns are having a flow on effect and impacting lifestyle choices (Figure 3) which will directly and indirectly shape the current and future energy ecosystem.

Figure 3: Actions taken or intended in the future to reduce environmental impact. Source: 2023 Gen Z and Millennial Survey, Deloitte

All of these distinct lifestyle choices, attitudinal, and behavioural characteristics of young people pose new questions for how we need to think about energy, its value, and use; not only as we transition to renewables and net zero, but as the energy system continually evolves and develops over time. This means reflecting on the future of transport and the use of EVs, how energy is negotiated inside the home, and the barriers for rental accommodation in accessing energy infrastructure. We must also think about Gen Z’s high digital literacy and comfort with technology and how this will influence different views towards automation and energy technology in the home.

We often hear that the energy transition must be inclusive to make sure no one gets left behind. That we need to hear the voices and experiences of those living regionally or remotely, of single parent households, people under financial pressure, victims of family domestic violence, women, First Nations Peoples, refugees, immigrants, renters, people living with disabilities - the list could go on. But we need to make sure that the perspectives of young people are also included. When deciding the future direction of our energy system, it is time to move away from imagining what a theoretical person living in this ‘future scenario’ would want, and ask, and listen to the people who are actually going to live through it. This is the best way to ‘future-proof’ our energy system.