How do Australians feel about new and existing energy technology? What appliances and devices are they buying? How and when are they using them? And how willing are they to change their energy usage?

These questions – and the answers to them – are critical for all who are engaged in planning, running, regulating and creating policy around our transitioning energy system.

They are also key questions for Australians themselves. The more each of us can understand how we and our neighbours use and want to use electricity, the more actively we can play a part in bringing about a future system that meets our values, needs and expectations.

That’s why we have created…

The Energy Consumer Behaviour Survey

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqnB4jA6BYY

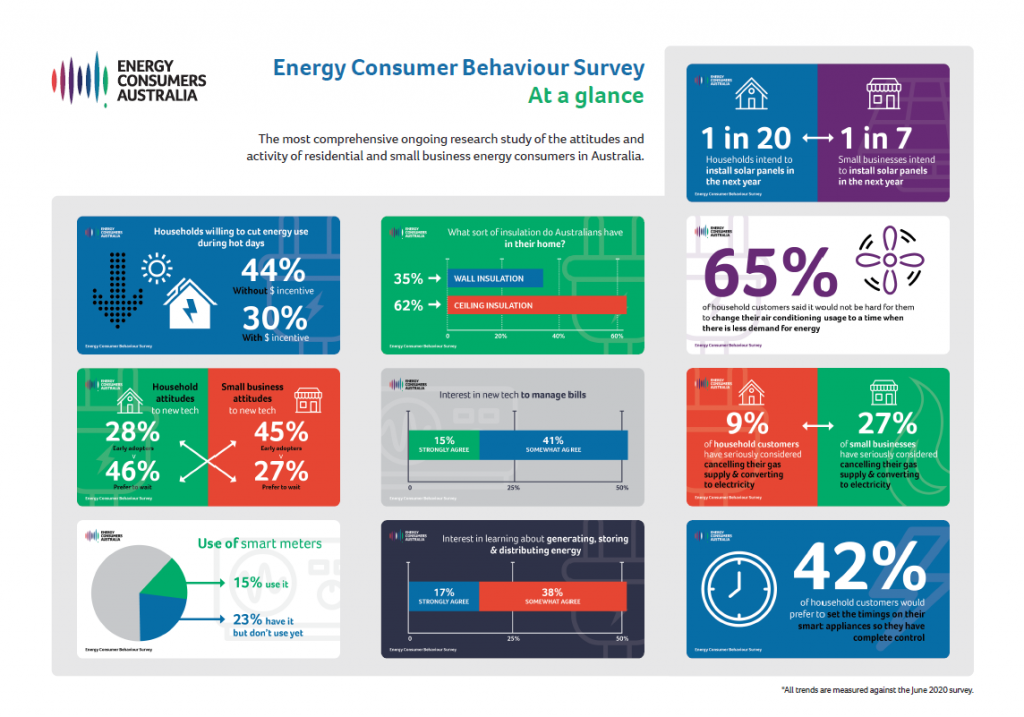

The Energy Consumers Behaviour Survey (ECBS) is a new study commissioned by Energy Consumers Australia and carried out by Essential Research. A companion piece to the Energy Consumer Sentiment Survey (ECSS), the most comprehensive ongoing research study of what residential and small business energy consumers think and feel about energy - this new survey will report annually on how Australians behave and plan to behave when it comes to decisions and social practices around energy use. It also includes questions that will contribute to the Digital Energy Futures study through our partnership with Monash University.

And the results are in

The survey finds that the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly reshaped not just how Australians are using energy but how they feel about their use.

- 41% of respondents say their household has become more interested in reducing energy use since the pandemic.

- 59% say they are cooking at home more.

- 40% say their house uses more heating and cooling since the pandemic

While some of these impacts may be temporary, others appear more lasting. The past 12 months have accelerated a move, already underway, towards the proliferation of devices and appliances in Australian homes.

- 52% say their household has more digital devices running than 5-10 years ago

- 42% say their kitchen has a wider variety of appliances than 5-10 years ago.

When we use energy

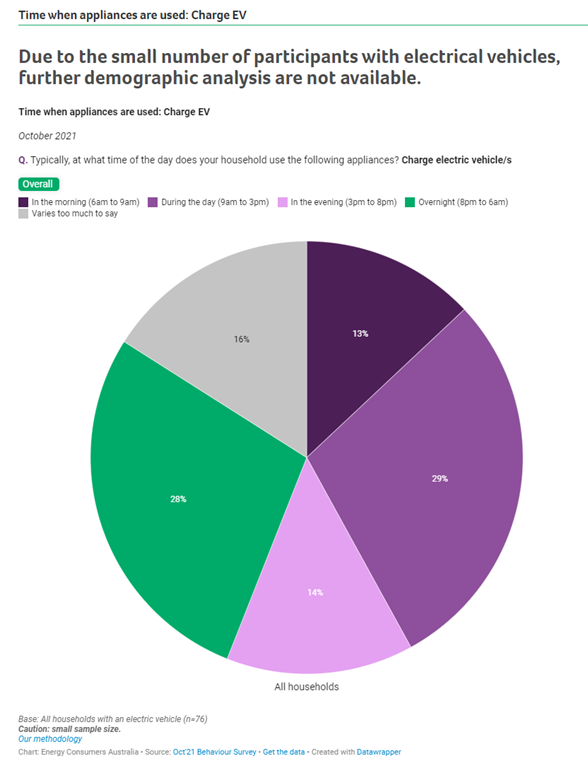

The survey looks at when people use various appliances to help gauge current and future demand for energy during peak times, generally in the morning and evening. It finds more than half of respondents with an electric vehicle charge it during off peak times, generally during the day or overnight. While the sample size is small, this is a promising trend from a network planning perspective, as during these times EV charging isn’t placing additional stress or demand on the grid.

Using energy-intensive appliances during peak times may present challenges to the operation of the system. If we can shift some of that energy use to other times of day without inconveniencing or disadvantaging consumers, the pressure to add expensive new infrastructure to the system will be reduced (helping to avoid higher energy bills). Shifting energy usage to the middle of the day, where possible, will also allow consumers to access the abundant, clean and cheap energy being generated on the rooftops of almost 3 million households. So how hard might that task be?

Changing our energy behaviour

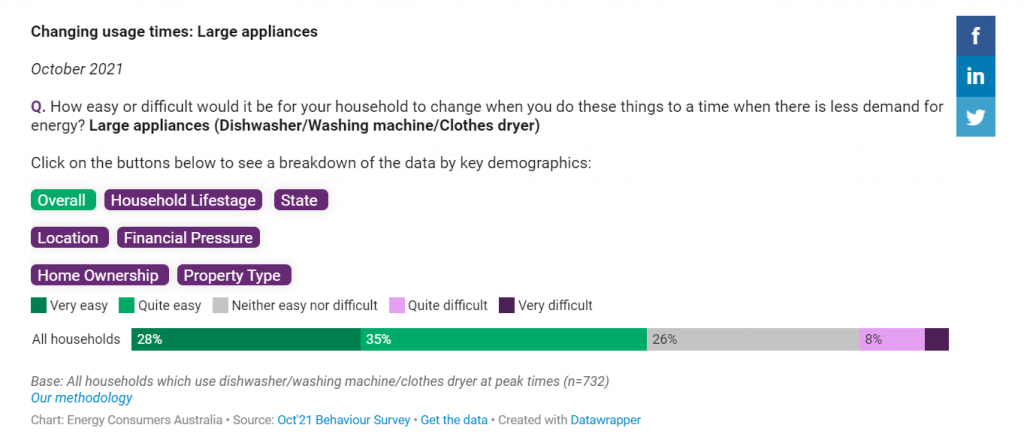

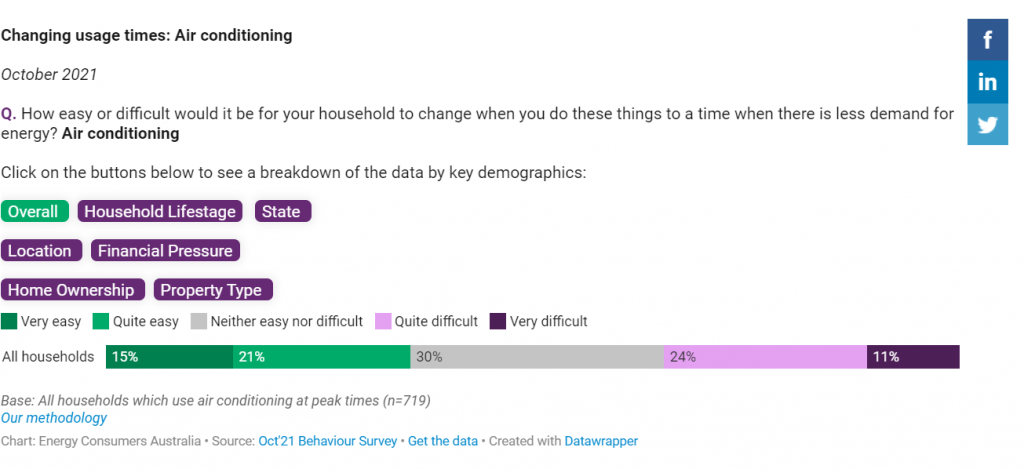

Most householders with dishwashers/washing machine or clothes dryers, said that it would be easy for them to change the time they use those devices to off-peak times, when there is less demand for electricity. Changing air conditioning was seen as the most challenging major appliance to shift use, with 35% of respondents indicating that it would be difficult.

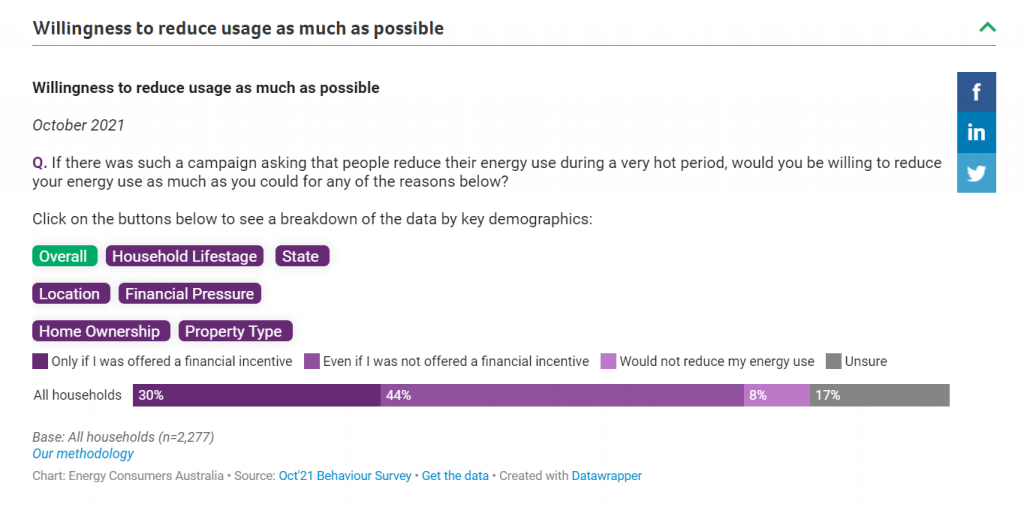

What might motivate consumers to change their behaviour? We asked households if they would reduce or shift their use during peak demand on a hot day. Around 30% of respondents said they would only reduce or shift their use if given a financial incentive. Interestingly, 44% said they would reduce even if not offered a financial incentive.

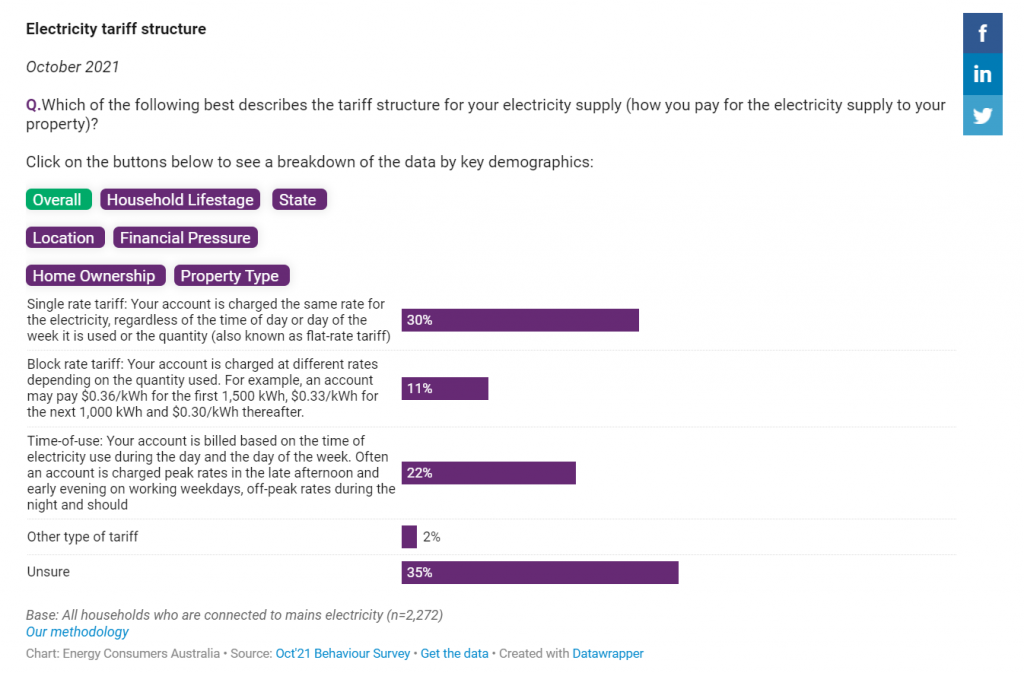

What about ongoing changes to energy usage? One proposed approach to changing energy usage patterns on a more permanent basis is adjusting the tariff structure that underlies consumer bills to incentivise lower usage at peak times (for example, charging a higher usage rate at peak times and a lower usage rate at off-peak times). But behavioural responses to tariffs are dependent on the broad engagement and understanding consumers have with the way they are charged for electricity. Nearly 1 in 3 respondents said they did not know the tariff structure of their energy plan. It is also dependant on consumers seeing the results of their actions in near-real time, which is challenging when bills are received every three months. This suggests that further work is required by the industry to motivate, reward and inform consumers.

Interest in Smart Devices

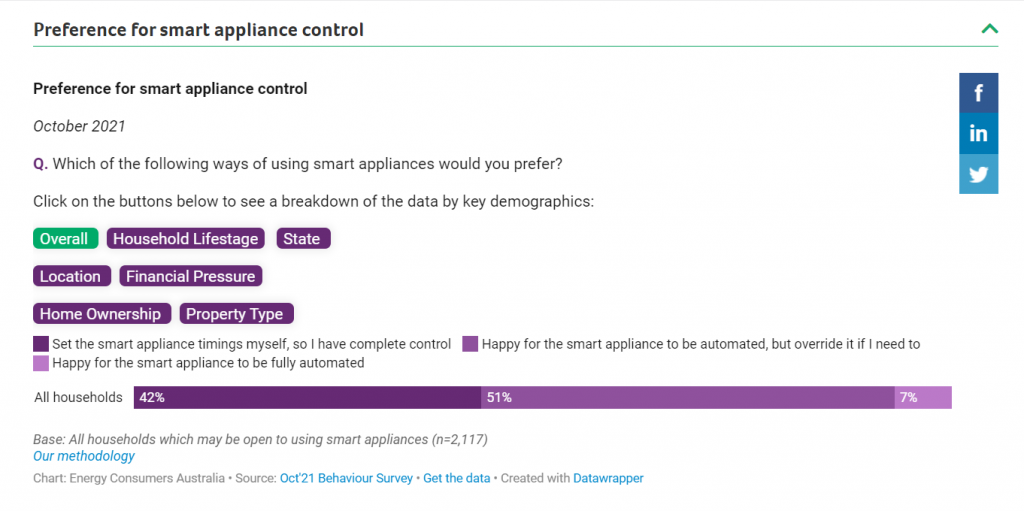

Smart devices have been coming into the market with the capacity to be automated. By allowing these devices to be automated, they can be set to run at times when energy costs are low, helping to bring down bills. However, some consumers may not like to have their devices running this way, as it removes the ability for autonomy over their energy use. We asked respondents how much control or automation they would want to have over these appliances. Only 7% of respondents said they would be happy for their appliances to be fully automated, compared to 42% saying they would want complete control. However, 51% said they would be happy for the appliances to be automated as long as they had the option of overriding if needed.

Ask. Don't Assume

Our first ever ECBS has given us a look into how Australians use energy and devices now and how they plan to use energy and devices in the future. The results reveal two important facts: consumers do not always respond as we expect them to, and consumer needs and values are diverse. To date, policy making, network and system planning have relied on the opposite assumptions – that consumers will respond to financial incentives and that there is such a thing as a representative or average customer. Continuing with this approach and relying on these assumptions could result in ineffective policy at best, and additional costs to consumers at worst.

Energy is so deeply tied to living and wellbeing and we can’t expect consumers to compromise on comfort or daily functioning for the sake of saving some money (or out of some altruistic desire to support the grid). Refocussing our attention to how consumers use and value energy as well as understanding consumer behaviour is essential for developing flexible regulatory frameworks that cater for the differences we see emerging in the survey, and better target areas consumers are saying they are willing to engage with. This understanding of consumer behaviour is becoming increasingly important as we navigate system requirements with customer preferences. Indeed, a challenging task, but one we are confidence the industry is able to tackle.